Superior View A view point on Brockway Mountain overlooks Lake Superior. © Michael George

Don Piche was not exactly surprised when, in 2021, he learned that a sizable chunk of Michigan's Keweenaw Peninsula was put up for sale. Those 32,000 acres of forestland—along with much of the peninsula—have a long history of changing ownership at the hands of big industries. But Piche, the chairman of the Keweenaw County board of commissioners and a lifelong resident of the area, was afraid of what this latest sale could mean for his constituents.

For generations, the people of the Keweenaw Peninsula had seen local land bought and sold by moneyed out-of-state interests. The Keweenaw, which extends north into Lake Superior from the western end of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, was once famous for having the largest deposit of native copper ore anywhere in the world. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, its mines employed thousands of European immigrants and created fortunes for investors back East. As the copper industry wound down after World War II, timber companies held Keweenaw forests to manage supply chain risk. When demand for wood products began falling in the late 20th century, they sold the land off to large investment firms.

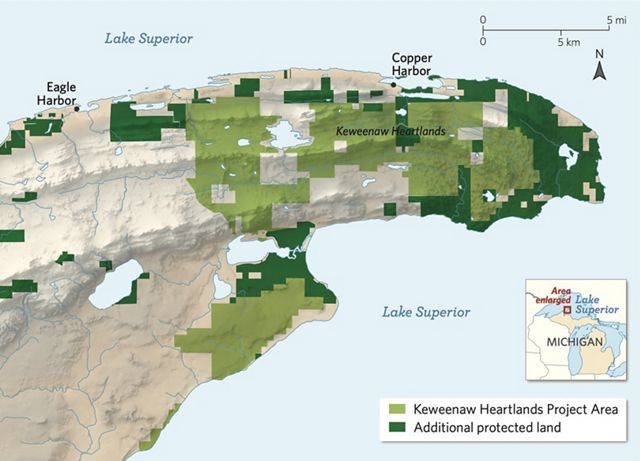

Who owned the land on paper, however, never made much difference to local residents. For as long as anyone could remember, the public had been allowed to use the forest for recreation, whether hiking, hunting and fishing, or harvesting the delicate, ruby-red thimbleberries that grow wild in sunny clearings. Laced with dozens of miles of ATV and snowmobile trails—all diligently maintained by volunteer clubs—this chunk of wilderness going up for sale, known as the Keweenaw Heartlands, had also become a key asset for the region’s tourism industry, which today is the top economic driver in Keweenaw County. And the land is beloved by the roughly 2,000 residents of Michigan’s least populous county, who derive a sense of identity from their ties to the natural world.

“The culture here’s always been about wanting to be out in the bush—hunting, fishing, riding ATVs and snowmobiles, whatever it may be,” Piche says over a plate of eggs at Slim’s Cafe, a popular breakfast spot in the former mining town of Mohawk. “People who have lived here all their life … are under the impression, just because they’ve been able to use it for years, that it’s public land.”

The tracts that went up for sale in 2021 had once belonged to the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, which had been one of the copper industry’s biggest players. Its most recent owners, based in New York, had announced they would be open to selling the entire acreage in a single deal or in smaller sales, including for development.

“[That land] being parceled off would’ve been catastrophic for the county,” Piche says flatly. “That would’ve been a death knell.”

What Keweenaw residents didn’t know then was that the sale also represented an opportunity for them to become true stewards of their land. Over the next few years, they would partner with The Nature Conservancy to preserve one of the least-fragmented stretches of forest in the Midwest, a place that’s globally valuable for its role in climate resiliency and in keeping the world’s largest freshwater system pristine. They would get to protect everything they love about their home, while building a brighter future for a community that has seen more than its share of hardship.

At the time, though, all they knew was that they needed some help.

TNC moves fast to save the Keweenaw

At first, many were hopeful that the state of Michigan would save the land. Members of the Keweenaw Outdoor Recreation Coalition, a local advocacy group, wrote to their representatives in Lansing, asking that the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) acquire the property. But the response was discouraging: Officials told them the department’s budget was already overstretched.

Meanwhile, TNC had a longstanding presence on the Keweenaw Peninsula dating back to a conservation deal in 1975. More recently, in the early 2000s, it had worked with the DNR to protect land at the peninsula’s tip, including 9 miles of Lake Superior shoreline. In 2001 it preserved Mount Baldy, a peak near the village of Eagle Harbor. And since 1982, the 1,200-acre Mary Macdonald Preserve at Horseshoe Harbor has protected an evergreen forest draped in rare bearded lichen and a cluster of billion-year-old stromatolites—cushion-shaped fossils formed by Precambrian microorganisms.

The Keweenaw parcels presented an unexpected opportunity for TNC to purchase land, says Helen Taylor, TNC’s state director for Michigan. And given the Keweenaw’s importance to the organization’s biodiversity and climate goals, the chance to protect so much intact forest was one the nonprofit couldn’t resist. So when the state passed on purchasing the land, TNC stepped up—with specific intentions.

“We made it clear we were not going to be long-term landowners,” Taylor says. “The key was to secure the land and then figure it out.”

In October 2022, TNC closed a deal to buy 22,700 acres of the Keweenaw Heartlands, with the purchase of another 9,800 finalized by the end of the year. But that was only the beginning—the next steps would be up to the local community.

Shaping the Keweenaw

Approximately 1.1 billion years ago, the core of North America began to split apart. Out of the growing rift poured floods of lava, which cooled into a horseshoe-shaped scar extending over 1,800 miles from modern-day Kansas up through Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and down again to Detroit. At its epicenter, the accumulated volcanic rock collapsed beneath its own weight, forming a deep basin that would eventually become Lake Superior. The Keweenaw Peninsula forms one rim of this basin, with Isle Royale—a narrow island set close to the Canadian shore—its smaller twin.

Huge basalt boulders, a relic of those ancient eruptions, stud the Keweenaw’s shoreline, and volcanic bedrock emerges beneath well-worn forest trails. Over eons, pockets of gas in the ancient lava that makes up much of the Keweenaw Peninsula filled with minerals, which formed colorful agates and the largest deposit of pure copper anywhere in the world.

This unique geology has long drawn humans to the remote peninsula. Native Americans excavated copper here beginning some 7,000 years ago; their jewelry and other trade goods have been found at archaeological sites as far away as New England. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Keweenaw mines employed immigrants, armed the Union in the Civil War and fueled American electrification.

The Keweenaw Heartlands property, which spans an area more than twice the size of Manhattan, is at its finest in late September, when the trees show their colors: bronze beech, bright-orange sugar maples, brilliant yellow bigtooth and quaking aspen. Every so often, a century-old smokestack pokes out of the canopy—remnants of copper smelting infrastructure that now offer shelter to birds like chimney swifts. Below ground, the myriad abandoned mine shafts are sometimes used by hibernating bats.

Since the purchase, TNC staff have been recording an inventory of the property’s natural and cultural features, including waterways; patches of high-quality habitat for animals like black bears, bobcats and migratory birds; and evidence of mining, both historic and prehistoric. Though the land has been logged over the years—in some places recently—the crew has also discovered some very old trees, specimens that survived not only axes and saws but also centuries of ice storms and strong winds blowing off Lake Superior. Defiant, gnarled oaks, cedars, balsam firs and white pines grow out of rocky clefts, their compact size belying their longevity. Meanwhile, rare lichens and determined little ferns colonize cliff faces, and the vegetation at higher elevations can resemble that of subarctic latitudes.

Adventures on Keweenaw Peninsula

Winter hits hard on the Keweenaw Peninsula, making the warmth of the summer sunshine and lake breezes a welcome change. Each year the population swells in the warm months as visitors join locals in a variety of outdoor adventures, cultural experiences and summer festivals.

Summer Adventures: At the annual Copper Harbor Trails Fest, mountain bikers and trail runners race in events like the steep downhill “Man Pants.” © Michael George

Fresh From the Oven: The monks at the Holy Protection Ukrainian Catholic Monastery run a popular bakery called the Jampot. Father Ambrose prepares baked goods before opening the shop for the day. © Michael George

Big Skies: Emma Lobert, a visitor from out of town, brought her own telescope to Brockway Mountain Lookout, hoping to see the northern lights. © Michael George

Casting Call: That same wildness has drawn fishing enthusiasts, like Paul Ritalco, who spent a day fishing the Montreal River where it lets out into Lake Superior. © Michael George

“It’s not like anything else that we have or manage, anywhere else in the Upper Peninsula,” says Emily Clegg, TNC’s director of land and water management for Michigan, explaining that the Keweenaw’s particular climate and geology have given rise to these unusual plant communities.

There’s plenty to see at ground level, but the best way to grasp the Heartlands’ sheer size is by viewing it from a higher point. On a warm, clear autumn morning, Clegg heads up Brockway Mountain, pausing at a 726-foot bluff near the community of Copper Harbor that TNC helped local officials preserve in 2013. To the north sparkles Lake Superior, with craggy Isle Royale—the least-visited national park in the contiguous 48 states, thanks to its remote location—sometimes visible in the distance. To the south, as far as the eye can see, are forested ridges and deep valleys with pockets of rich wetland, some of it deliberately engineered by a thriving population of beavers. Most of it is the Keweenaw Heartlands.

Clegg and her staff have spent much of their time here since the Heartlands purchase, negotiating rugged back roads and thick vegetation as they make the land’s intimate acquaintance. But looking out over all this newly preserved forest still gives Clegg a sense of pride and wonder.

“It’s just an awesome view from the top,” she says.

The new plan that keeps the Keweenaw Heartland for the people

For centuries, the Keweenaw’s residents made their living from this land, whether from the veins of copper that ran below it or the rich stocks of timber that lined its ridges. But protecting the Keweenaw Heartlands will mean leaning into a diversified forest economy that combines sustainable extraction with outdoor recreation. That combination is a shift that has brought new challenges to a region already struggling with problems common across rural America.

Robin Meneguzzo, executive director of the Keweenaw Community Foundation, can trace four generations of her family on the Keweenaw Peninsula. Many family members are still in the area. But beyond them, much of her own generation of residents has left to find opportunity elsewhere.

“Almost no friends of mine from high school have stayed,” she says. “Employment opportunities and just the remoteness makes it difficult—our closest metro is the Twin Cities. That’s a good six-hour drive.”

Those who have stayed struggle to purchase a home, she says, largely because even modest houses are often snatched up as vacation rentals. Meanwhile, Keweenaw County’s year-round population is less than half what it was a century ago. A small tax base puts a strain on local governments, whose budgets are already stretched by the special challenges of plowing several feet of snow every winter and rescuing people who get injured or lost in the wilderness.

When TNC purchased the Heartlands, local residents were relieved that the land would be protected from developers. But after decades of tough times, they also worried about what would come next. To help everyone figure that out, TNC brought in John Molinaro, an Ohio-based rural economic development consultant who has worked with communities all over the United States.

“We recognized that there were so many needs of the community that we were not aware of,” says Taylor, TNC’s Michigan state director. “We wanted to make sure that those lands do not impede those needs, and we hoped that this project would be a way to bring the community together.”

When Molinaro arrived in the Keweenaw in March 2022, he met with local business owners, outdoor recreation advocates, government officials and leaders of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community.

After 58 one-on-one interviews, 13 well-attended community meetings and more than 1,800 survey responses, Molinaro helped the community select a planning committee made up of local people, and a vision began to emerge. The land should be publicly owned, but it couldn’t be a drain on county and municipal budgets. It should be managed as a working forest, both for sustainable timber harvests that could provide revenue and jobs, and to generate carbon offset credits that would allow local people to benefit from their stewardship of a global resource. But the land’s economic value couldn’t come at the expense of its cultural importance: It would have to remain open to recreational users.

“The land is integrally tied to the people who live on it and rely on it for their lives, their livelihoods, their culture,” Molinaro says. “The Nature Conservancy has learned through its decades of experience that if you don’t engage the local people, then it doesn’t really matter what’s in your plan. The people had to feel like it was their plan—and it had to be honestly their plan.”

It’s an approach that Keweenaw residents, so used to being on the sidelines, deeply appreciated.

“We were very skeptical at the beginning,” says Don Piche. “But they’ve told us the truth through this whole process.”

Over the course of a year of discussion, the planning committee came up with a blueprint for a new governing body to manage the Heartlands. The current proposal will include trustees elected by Keweenaw County voters. It’s expected that the vast majority of the land will be overseen locally, with a smaller portion of it eventually owned by the state. The proposal, which also recommends a separate advisory board of people with expertise in conservation, historic stewardship, forestry, recreation and public safety, will ensure that the trustees take the Heartlands’ many uses into account. Once the new authority is up and running, likely within a couple years, it will take possession of the Heartlands.

“It’s going to take people who want to be involved and are passionate about it,” says Rich Probst Jr., a planning committee member and the supervisor of Eagle Harbor Township, located near the Keweenaw Peninsula’s tip. “It’s kind of a good place to be in, because you’re not really trying to follow anything. We’re trying to do something new.”

The whole process has been much like those old logging roads that crisscross the Heartlands: long, and not without bumps along the way—and when TNC and Keweenaw residents set out back in 2021, no one was quite sure where it would lead.

About the Creators

Amy Crawford is a freelance writer based in Michigan who writes about the environment, history and art for publications like Smithsonian and Slate.

Michael George is a photographer based in New York. His work has been featured in National Geographic, The New York Times and other publications.